New Jersey Gets a “D” For Fair School Funding. Does It Matter?

July 30, 2025

Newark High Schoolers Can’t Read So They’ll Watch ‘The Lego Movie’

August 12, 2025Are NJ Parents Of Students With Disabilities Finally Getting Some Power?

When my son Jonah was three years old, we had the first of those all-important sessions for students eligible for special education: the annual IEP (“Individualized Education Plan”) meeting, which lays out current levels of functioning, goals for that year, supports, therapies, and environment necessary to reach those goals, time spent with typical peers, transportation, etc.

Here is how it went: During Jonah’s weekly early intervention appointment (he was not quite three years old yet so our local district wasn’t responsible), a social worker called me over to a table, shoved a pile of papers at me, and told me to sign an IEP my husband and I had never seen before that said he would spend the next year at a county special services school we didn’t want him to attend.

That was 25 years ago and we’ve learned a lot, privileged as we are with the time and resources to ensure our son was receiving the necessary services to support his learning and development. But too often parents of children with disabilities — and older students themselves— are left out of the loop when IEPs are developed. This is despite the fact that parents, by law, are members of the IEP team and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act explicitly states “almost 30 years of research and experience has demonstrated that the education of children with disabilities can be made more effective by strengthening the role and responsibility of parents and ensuring that families of such children have meaningful opportunities to participate in the education of their children at school and at home.”

A new bill in New Jersey would require school districts to give parents those meaningful opportunities, at least around the edges. Jamie Epstein, a special education attorney, told NJ Ed Report, “I call it ‘the IEP team no longer being allowed to withhold the draft IEP from the parent prior to the IEP meeting Law.’”

Indeed, New Jersey Senate Bill 3982 would require school districts to provide parents with some important parts of IEPs two business days before IEP meetings (not enough time but better than nothing): academic /functional levels of performance, a list of all Child Study Team members who won’t be at the meeting and their narratives about what the student needs. It would also require districts to invite parents to offer suggestions, a right they’ve always had but is sometimes unexercised. Also the bill establishes an IEP Improvement Working Group that would “make recommendations to the Department of Education regarding the development and implementation of Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and the inclusion of parents in the process.”

This bill proposal is an acknowledgement of flaws in the process of developing educational programs for students who rely on a “free and public education” in the “least restrictive environment” but are, in too many instances, cheated out of that guarantee. Elizabeth Athos of Education Law Center notes, “because of limitations on the information provided,” parents may not “have had a chance to digest and understand” their student’s disability, needs, or IEP, preventing parents “meaningful participation” during those meetings.

It also may be in response to growing awareness of how many children qualify for special education services, 18% in NJ, or 240,000 students, one of the highest classification rates in the country. Autism rates are 1 in 29 children here, also the highest in the country. (No, it’s not vaccines.*) New Jersey stands out for having the highest national rate of segregating students with disabilities in separate schools.

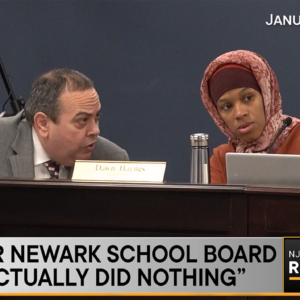

For example, the state found that Newark, our largest district, is “falling short” on managing IEPs, to the point where parents of some students with disabilities found out on the first day of school their children didn’t even have a placement despite the legally-binding nature of these documents. “The state department also found the district had problems with reporting in education plans, notifying parents of meetings, and missing meetings with parents and students with disabilities as part of responsibilities mandated under the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA).”

In Asbury Park, a staff member told NJ Ed Report, the district wasn’t providing parents with appropriate translators during IEP meetings. Senator Majority Leader Teresa Ruiz (who is sponsoring the bill) explained the new law would require districts “to at least have a document before a guardian so that they can go through and start making notes before the meeting… If English is your second language, it becomes even more difficult.”

Too often, students’ access to necessary services is dependent on the ability of their parents to know their rights in order to advocate effectively. This new law, while primarily a tweak, sets us in the right direction towards more equitable educational opportunities for children with disabilities.

*That autism rate is partly due to rising awareness, which is great. But also consider diagnostic creep due to social contagion, “Munchausen by internet,” and what Freddie de Boer calls the “gentrification of autism” which aggrandizes a debilitating condition to cute and quirky “neurodiversity” in our identity-driven culture. As we broaden our definition of autism, we diminish those who are most afflicted. Sometimes it really is a zero-sum game.