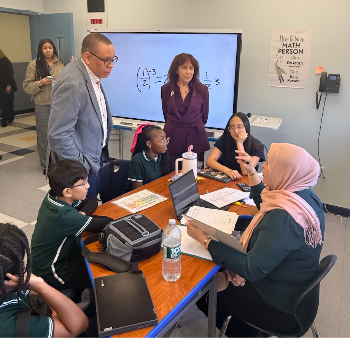

Lt. Gov. Dale Caldwell Tourns NJ Tutoring Corps’ World-Class Tutoring Center

January 22, 2026

Increasing Quality Instructional Time Requires Addressing Teacher Absenteeism

January 29, 2026Can Sherrill Get Past ‘Trump Sucks’ And Do Right By Kids?

Last week Andy Rotherham weighed in on a big educational decision facing Virginia’s Governor Abigail Spanberger and what she should do about the federal government’s new K-12 education tax credit program, part of the Trump Administration’s “Educational Choice for Children Act.” This program doesn’t create vouchers or Education Savings Accounts; instead it allows individuals to get a $1,700 federal tax credit for money given to non-profits providing scholarships for private school tuition, tutoring, books, services for kids with disabilities, and other education costs for families whose annual income is at or below 300 percent of their area’s median income. Rotherham argues former governor Glenn Youngkin did Spanberger a favor by opting into the tax credit program before he left office, leaving her with generous “optionality”: She can say, “we’re already in so we’ll mold our program to fit out state’s values” (unclear how much latitude there is because the feds have yet to release regulations) or she can align with the politics of Virginia’s teacher unions and cancel Youngkin’s (non-binding) bid. It’s her choice.

Circling home, what should New Jersey Gov. Mikie Sherrill do, given that Gov. Murphy, her predecessor, left office without leaving her the benefits of optionality afforded by Youngkin to Spanberger, her fellow Democratic centrist and former roommate?

I think the trade-offs are more difficult than they might appear, despite the teacher union’s antipathy towards school choice programs. First of all, as Rotherham says, Democratic governors who bow out will need a better excuse than “Trump sucks.” Why? Because by not participating they will be leaving federal money on the table, some of which will come from rich taxpayers (including those in New Jersey) who took that federal tax deduction. This is not a zero-sum game: opting in doesn’t affect regular funding streams. Instead, it’s all extra cash that, if NJ opts out, will go to other states that opted in. How do you explain that to the public? (From Jorge Elorza: “if a state does not opt in, then by default, the first $1,700 in every single federal taxpayer’s taxes is going to leave your state.”)

There is also this: During the campaign Sherrill referred regularly to problems with NJ’s state school system which, in many cases, relegates low-income students, disproportionately Black and Brown, to low-performing schools. She promised she’d work on boosting student performance— currently almost half of our kids can’t read at grade level and 40% can’t do math —and increasing equity among districts. During her inaugural address she said, “we’re going to shake up the status quo.”

What better way to shake it up than ignoring NJEA and status quo defenders (yes, they’ll have a collective cow but Sherrill is a Navy pilot, she can handle it!) and taking the money?

Sure, there is a lot of uncertainty about this program because we haven’t seen the regulations yet. Maybe it will be a non-starter once we do. But what’s the downside of opting in now and backing out later or, alternatively, waiting to see how we can use those tax credits for kids in our lowest-performing districts? (Chad Aldeman suggests blue state governors go with, “we’re going to give it a hard look once the regulations are finalized. While we would like to put our own stamp on it, we won’t say no if the federal government wants to invest in our state’s young people.”)

For instance, what if those funds can be used to expand tutoring opportunities or special education services or other Democratically-acceptable programs? What if we can ensure accountability and transparency for those scholarship-granting organizations? Sherrill wouldn’t be lonely in this position: Colorado’s governor Jared Polis, a Democrat, has already opted in. Arne Duncan, President Obama’s former Ed Secretary, wrote in the Washington Post that the tax credit program would fund “a range of services already embraced by blue-state leaders, such as tutoring, transportation, special-education services and learning technology. It’s a chance to show voters that they’re willing to do what it takes to deliver for students and families, no matter where the ideas originate.”

Gov. Sherrill seems to get the urgency around improving NJ’s school system; for instance, she chose Lily Laux, formerly second-in-command of Texas’s Education Department, who credits part of the state’s improved student outcomes to more “top-down” strategies than we’re used to here. (For example, requiring districts to choose one of several vetted science of reading curricula. See more from Julie O’Connor on this.)

And maybe, just maybe, Sherrill knows that what hasn’t worked before (diminishing accountability, lowering standards, throwing money at the problem) won’t work now.

Rotherham concludes, referring to Spanberger although he could have been talking about Sherrill, “Governors who opt out had better point to an education policy agenda so robust around genuine school improvement that it offsets the politics. ‘We didn’t do X because we are doing Y’ can work—but only if Y isn’t the same old weak soup.”

Barring the quick emergence of a robust plan for genuine school improvement, maybe we serve NJ’s students best by holding our nose and leaving our options open. Is Sherrill clear-headed and child-centric enough to get to “yes”? Or at least to “maybe”? Here’s hoping.