iLearn Schools Honored as 2024 Charter School Champion of the Year

April 29, 2024

How Can We Ensure Students With Disabilities Have an Inclusive Education?

April 30, 2024As Goes Jackson, So Goes Jersey

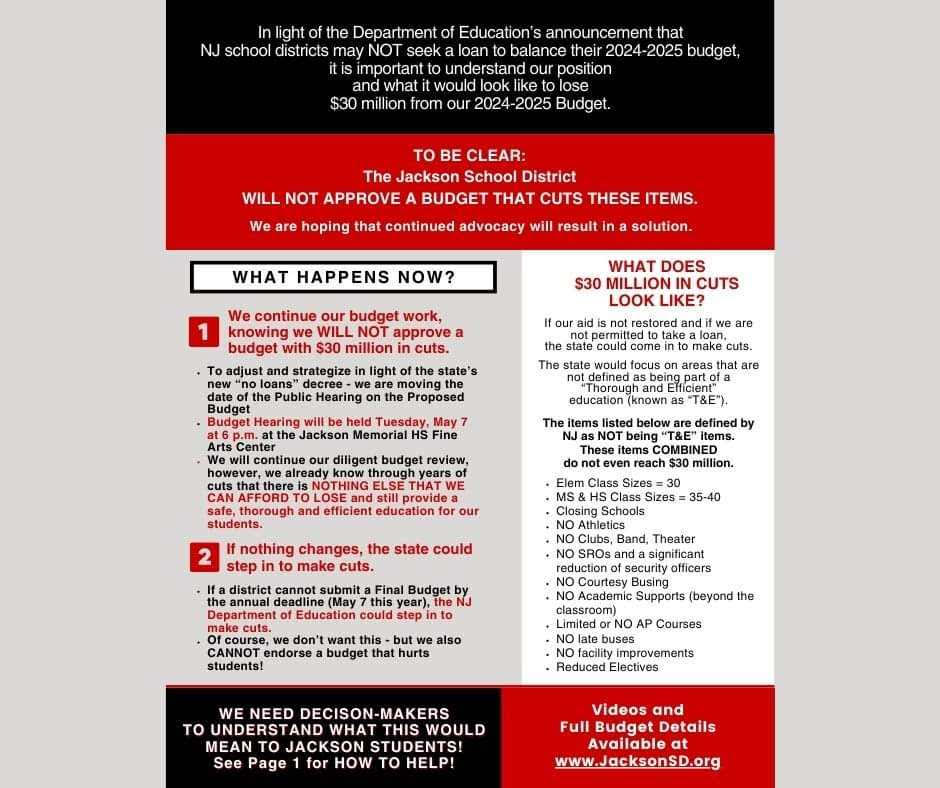

Jackson Township Public Schools District is furious. Superintendent Nicole Pormilli and the school board say slashed state aid –all in, $22.4 million since 2018—has resulted in their inability to provide 7,535 students with a constitutionally-guaranteed “thorough and efficient” education. Without a $30 million loan from the state, 17 percent of its 2024-25 operating budget, the district will have to raise high school class sizes to 40 students and cut all clubs, athletics, AP courses, student support, courtesy busing, and extra-curricular activities. Jackson’s newly-designed homepage pleads with residents —who voted down a $4 million referendum in October—to lobby Gov. Phil Murphy and the State Department of Education who, they say, have told them (see image at the bottom) “NJ districts MAY NOT seek a loan to balance their 2024-2025 budget.”

It’s a little more complicated than that, although Jackson is indeed in a fiscal jam with implications for many of New Jersey’s 600 other school districts.

Let’s start with an simpler question: Has the DOE indeed mandated that districts “MAY NOT seek a loan”?” Not according to the DOE. In an emailed response to NJER, spokesman Michael Yaple writes,

“Reports of any blanket determinations seem to reflect a misunderstanding of the school district budget development process. A school district does not simply request additional state funding to balance its subsequent year budget submission. In extremely rare instances, and only when certain fiscal conditions are met, State law empowers the Commissioner of Education to recommend to the State Treasurer an approval of an ‘advance state aid payment’ to ensure the provision of a thorough and efficient education in the current budget year, after adoption of a balanced budget.”

In other words, loans are not possible, just “advance state payments,” and only in “extremely rare instances.” (Example: Lakewood, although everyone knows it will never pay back those “advances”.). In fact, last year Jackson got a $10 million advance payment from the DOE (along with the ongoing costs of a Fiscal State Monitor, Carole Morris, late of Asbury Park).

Is Jackson taxing homeowners at the maximum rate in order to raise more revenue?

Not really. Under our state school funding formula, Jackson has been taxing residents less than it could (“Local Fair Share”) and now it’s stuck because the 2010 law called S2 disallows districts from raising school taxes more than two percent a year (with a few exceptions for increases in enrollment and healthcare costs). Therefore, part of Jackson’s campaign is to get the State Legislature to overturn S2. (There is currently a bill proposal that would do just that, as well as another bill that would restore much of the state aid cut in Murphy’s FY2425 budget.)

In fact, according to Jeff Bennett, Jackson’s 2023-24 tax levy was $30 million below its Local Fair Share, the exact amount of its deficit.

Is Jackson having some sort of enrollment spike that would account for its need for more money?

No, over the last decade the number of students in Jackson has dropped 18%. That is a big reason why its state state aid allotment has dropped..

There is a spike of students, but that’s non-public school students. As Lakewood runs out of room, nearby townships like Jackson, Brick, Howell, and Toms River are seeing increases in the number of private school students for whom they must provide transportation and, when eligible, special education services. In 2017, Superintendent Pormilli told legislators, Jackson had to pay for 655 non-public school students to get back and forth to school. Next year the district will pay $4 million for the transportation of 5,584 non-public students, an increase of 752% in seven years. (Note: the state compensates districts for private school busing, about $500 per student.)

To make budgeting even more difficult, Jackson has seen an increase in in-district English Language Learners who are entitled to specialized instruction at additional cost (although the state aid formula is supposed to account for that).

Let’s step back for a statewide look.

Traditional district enrollment is dropping throughout the state (the country too) as birth rates decline:

As we start to educate fewer students than we have in the past, districts may need to consolidate by closing under-used school buildings or even merging with other districts. This is an especially hard sell in New Jersey, where many residents revere local control.

Finally, Jackson is facing the fiscal cliff—the cessation of COVID federal emergency funding (also called ESSER funding) in September—just like all other districts. From the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities:

“The expiration of these resources will create a fiscal cliff for school districts, which will need to figure out how to make up for the lost dollars or significantly reduce services…[T]he loss of ESSER funds could have severe implications for students, including risking teacher layoffs, school closures, and the loss of crucial student programming…the impact will be nationwide.”

Yes, Jackson needs more money to keep class size reasonable and maintain essential programming. Yet short-term fixes—“advance payments” from the DOE or reversing Gov. Murphy’s school aid cuts—merely delay real solutions that plan for a changed public education landscape. That is a lot harder than an extra check from the DOE.