NJ DOE Watch: You Thought It Was Bad in Student Services? Check Out the Assessment Division’s Dysfunction.

November 28, 2018

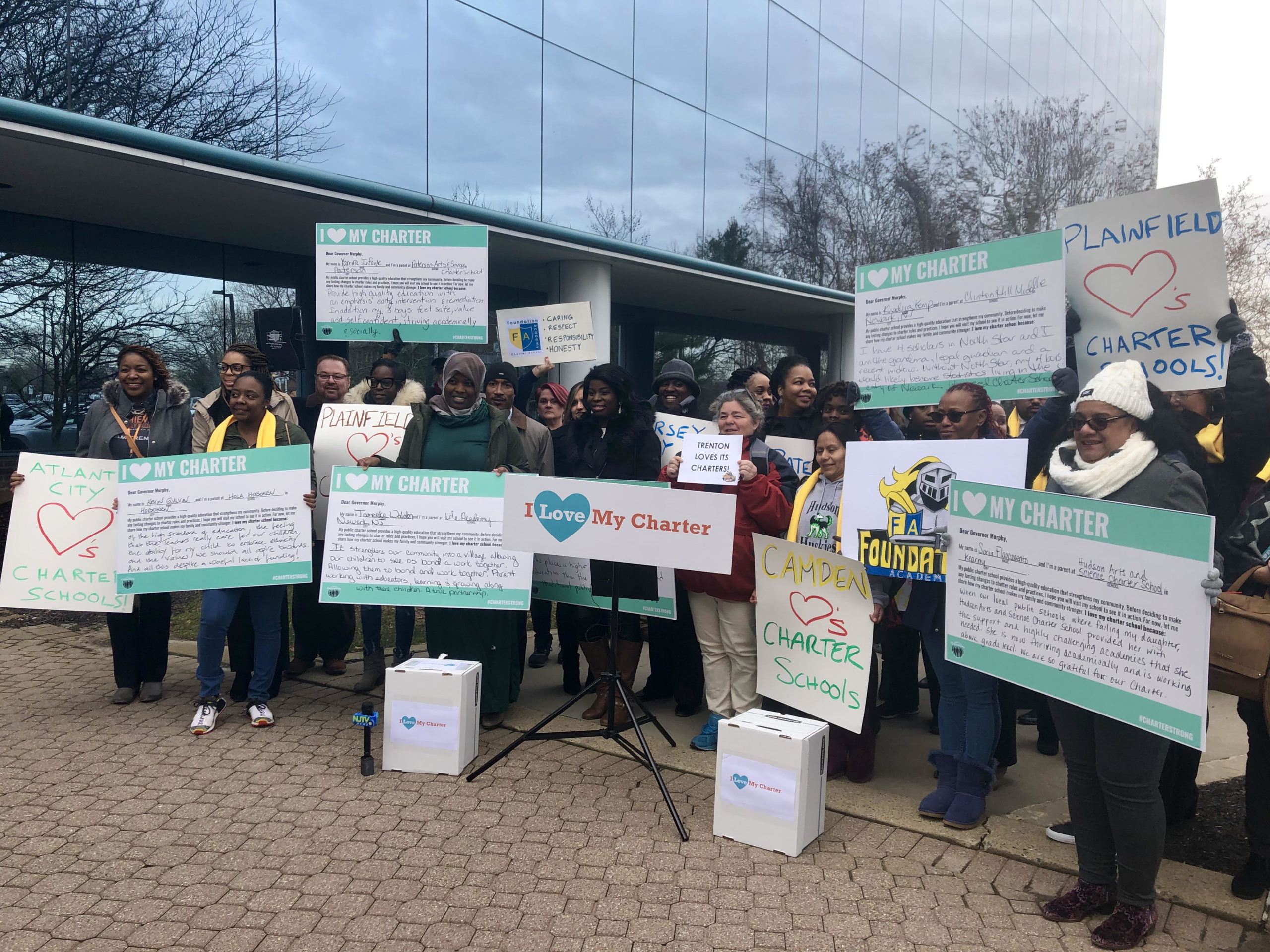

You Want An Authentic Charter School Review? New Jersey Has One Now! Parents Brave the Cold To Speak Truth to Comm. Repollet

December 6, 2018We Need To Talk About Race When We Talk About New Jersey Charter Schools.

I’ve been thinking about race this weekend, probably because NJ Advance Media just came out with The Force Report, which describes this state’s broken criminal justice system. According to the journalists, who worked for 16 months to complete this project, in New Jersey Black people are more than three times as likely as white people to face police use of force, which includes “compliance holds,” “takedowns,” using “open hand strikes or closed punches,” “leg strikes,” pepper spray, batons, “sic[cing] a police dog on a suspect,” stun guns, and firing of weapons.

That “three times as likely” is just the state average: in South Orange Black people are nine times as likely as white people to face police use of force and in Lakewood it’s 21 times more likely.

For me, this disproportionality converges with the Charter School Law Review, currently being conducted by the New Jersey Department of Education.

Why? Because — let’s just say it — the vast majority of charter school students in New Jersey, 86.7 percent, are Black or Brown. (Seventy-two percent are low-income.) When the DOE Commissioner, our sole charter authorizer, decided to reject all charter school applicants in the last round, the parents who lost the opportunity to make better educational choices for their children were almost all Black or Brown.

I know it’s hard to talk about race. But when we talk about charter schools and equity, just like when we talk about criminal justice and equity, we can’t ignore the disproportionate impact on children and families of color.

Except that we do.

I’m old. I was born in the tail end of the Baby Boom and grew up in a time when it was considered virtuous to visit with a group of people and claim you “didn’t notice” if someone was Black or white or brown, noble to insist you were “color-blind.” I work at a non-profit that employs a lot of millennials, many of color. They’d laugh me out of the room if I insisted that the color of our skin doesn’t affect who we are, what obstacles we face, how the world sees us and we see the world.

And so, if the DOE is serious about having an honest discussion about charter schools, than we have to talk about the demographics of the 50,000 children these schools serve.

If you attend the annual NJ Parent Summit, which I do, you may notice that almost all the charter school moms and dads there are parents of color. If you go to the #CharterStrong Facebook page, you’ll see photos of parents and students, almost all of color. If you go to the pro-charter Parents Engaging Parents page, you’ll see photos of parents and students, almost all of color.

This is not true of every charter school in NJ. At Princeton Charter School, one of our first charters, students are 54 percent white and 31 percent Asian. But this is the exception, not the rule, especially since almost all of our charter schools are clustered in low-income cities where most residents are Black or Brown. This disproportionality — the fact that charters serve many more students of color than white students — must be a key factor in any discussion of the future of NJ’s charter school law and the DOE’s current stance.

When Ed.Comm. Repollet decided to not approve any charter school applicants in the last round (and ignore the standard DOE process), he was almost exclusively slashing public school choice for Black and Brown families. (White families, who tend to be wealthier, freely exercise NJ’s most common form of public school choice, moving to towns with better school districts) When Gov. Murphy announced a “pause” (or a “stealth moratorium”) on authorizations of new charter schools, he was almost exclusively slashing public school choice for Black and Brown families.

I’m not saying that racial disproportionality in criminal justice is equivalent to racial disproportionality in parents’ ability to enroll their children in better schools. But to deny any connection is to deny reality.

Yes, race is hard to talk about. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk about it. In the case of the charter school review process, we must. If the DOE, state legislators, the State Board of Education, and our Governor refuse to consider the disproportionate impact of the current charter moratorium on students of color, then we efface those 50,000 students and the 35,000 who sit on wait lists. They deserve better. They always have. Let’s have the wisdom and integrity to recognize reality.