Murphy Signs Legislation to Expand Access to Mental Health Care in K-12 Schools

July 13, 2023

Sikh Youth Alliance Celebrates Passage of Resolution to Include Sikhism Instruction in Schools

July 14, 2023River Edge Is America: Here’s How Parents Stop Trusting Their Schools

It’s a truism that over the last few years Americans have lost trust in public institutions; for instance, a new Gallup Poll says only 26% of Americans trust public schools. One result is that many parents, once content to delegate education to their local districts, are recognizing they have power to influence how and what their children learn, and also to influence decisions school boards make. Headlines often focus on the more sensational aspects of this new-found power, like debates about culture wars (book bans, LGBTQ rights, structural racism) and the rivalry between parent-centered groups (Moms for Liberty and National Parents Union). But sometimes parents challenge more basic issues and, in the course of their campaign, bring to light the capacity they have to effect change.

Case study: River Edge Public Schools, a 1,162-student two-school K-6 district located in a 1.8 square mile borough of Bergen County. Given high achievement and high income levels, this district could be a model of complacency. Instead, it has descended into chaos.

Why?

According to the eleven parents I spoke with, Superintendent Cathy Danahy, who they say controls the school board, is trying to railroad through a reconfiguration of the two schools. Instead of Cherry Hill Elementary School and Roosevelt Elementary School both educating K-6th graders, all pre-K through third-graders will go to Cherry Hill and all fourth-sixth graders will go to Roosevelt. In response, much of the community is irate, citing police reports that warn of traffic safety concerns, incomplete cost analyses, and the district’s ever-revolving catalog of fact-free justifications for this structural shift.

Perhaps in pre-COVID days parents would have deferred to the judgment of school officials. Now? They’re on fire.

It didn’t have to be this way, or nearly as bad. Sure, across the country remote instruction gave parents an insider’s view of classrooms that may have soured them a bit on school quality. In River Edge, according to parents, trust has faded because district officials are distributing misleading information in order to silence parents’ voices.

It’s not working. As such, River Edge becomes an instructional model of what school leaders shouldn’t do when faced with what increasingly looks like a rebellion.

Here is an abbreviated timeline for what could be a book-length study of how to create distrust within even the smallest school district.

- In May 2022 the district issued a State of the School presentation arguing they need to reconfigure the schools due to a “lack of space” for appropriate special education programs and other percolating issues.

- In December 2022, the Finance and Facilities Committee proposed the reconfiguration in order to solve these space issues, as well as what they said were disproportionate class sizes between the two schools, teachers losing time having to travel between buildings, and lack of parking spaces for teachers.

- In January 2023 the district issued a website and a video reviewing the Board’s research, with much emphasis on a state report that said the district was out of compliance with special education law because too many of the 126 classified students spend time in restrictive self-contained classrooms. Other benefits include more time for teacher collaboration, expansion of programs, and taxpayer benefits. The district acknowledged potential problems: for instance, regarding increased car traffic at Cherry Hill, the superintendent suggested a “valet service” or a “shuttle bus.”

The parents of River Edge went to work, mining state databases and issuing Open Public Records requests. They posted a Change.org petition (it has 840 signatures) demanding the district “stop reconfiguration and request that the Superintendent and Board of Education present alternative solutions to achieve optimal educational and operational benefit.”

Here’s what they told me:

Compliance: The district is in compliance with the state special education metrics. River Edge was cited last year for having too many students without adequate access to mainstream classrooms; the district will be in compliance in September. In fact, adding additional self-contained classrooms could put them out of compliance again. (Note: According to the state Education Department database, of River Edge’s 126 special education students, half are classified with Specific Learning Disabilities and Speech/Language Impairments who are typically placed in general education classrooms. The district already has five self-contained classrooms.) Parent Erin Burns, a special education teacher in another district, told me there were multiple options for creating better special education programs without reconfiguring schools but the Board isn’t interested.

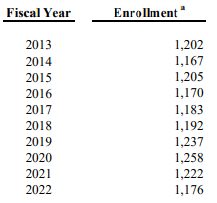

Space Issues: River Edge does not seem to have a lack of space. Class sizes are small, all below state caps. According to a demographic survey performed by Statistical Forecasting LLC in June 2022, when “historical enrollments (PK-6) were analyzed…enrollments have declined to 1,170 in 2021-2022. In the past year, there has been a decline of 80 students…the district has experienced negative kindergarten replacement in seven of the last nine years…[E]nrollment is projected to be 1,069 in 2026-27, which would be a decline of 101 students from the 2021-22.” Also, the reconfiguration doesn’t add any space.

Here are current enrollment trends:

Safety Concerns: A primary concern among parents is prospective safety problems: if siblings are assigned to different schools, parents will need to do two drop-offs which could cause additional traffic. Indeed a report from Police Chief Michael Walker says the reconfiguration would have negative impacts on traffic, crossing guards, and student walkers. The five-page report concludes that, while he respects Danahy and her belief that reconfiguration will address educational concerns, the police department “cannot support the reconfiguration plan for the Roosevelt and Cherry Hill schools.” (The Board solicited a second report that said there would be a 45% increase in traffic but everything would be fine. Parents aren’t buying it.)

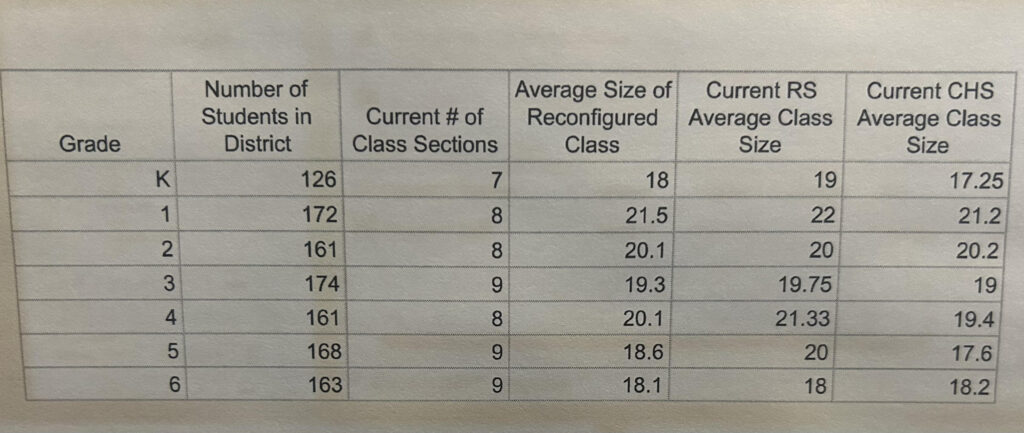

Class Size Discrepancies: After some digging, parents shared this list that shows there is not, in fact, a disproportionate class size difference between the two schools. (“RS” is Roosevelt School, “CHS” is Cherry Hill School.)

Teaching Time: Parent Kiersten Eng calculated that 15 teachers teach in both schools—but on different days, which shows there is no time lost on traveling between the schools. “Definitely not the picture Ms. Danahy painted to the board and the public,” she told me. [Correction: a few of these teachers spend half a day at each school.]]

Cost: Part of due diligence was a promised cost analysis. At the February Board meeting, president Eun Kang conceded (1.08) it had never been done.

As tensions increased, the Board seemed to be gracefully handling the long periods of public comment. Then in June the Board president announced a new policy: public comment would be limited to fifteen minutes. (I have never heard of a board limiting comments to fifteen minutes.)

At the June board meeting, parent Sebastian Muscarella appeared to speak for much of the crowd; his remarks generated loud applause as he described the new dynamic between parents and school leaders:

“You stare at us like we don’t matter. This is your public and children telling you you’re going down the wrong path.” Referring to Danahy, he continued, “no one person should have so much autonomy and authority. But we are fighters and will stand our ground.”

When Muscarella tried to hand the Board the petition, president Eun Kang publicly belittled the numbers. When the Board discussed whether they needed to vote on the reconfiguration, they looked to the superintendent to tell them what to do. (The vote will most likely occur on July 19th at the next school board meeting.)

“It feels like we’re being silenced,” said a frustrated parent, Adam Andrew. “You turn a deaf ear to the police department’s concerns about safety. There’s a word for that: negligence. We are losing faith in our school board. With negligence comes accountability.” (Kang’s reply: “We are elected officials and you have to trust us to make the right decisions.”)

This past January, in a letter to the community, Danahy reassured the public,: “My goal will always be full transparency.”

But the public doesn’t believe her, nor do they trust the board of education.(One possible exception is board member Liz Brown, who said in June, “I’m not comfortable voting [on the reconfiguration]. We don’t have all the information.”)

In a statement to NJ Ed Report, Superintendent Danahy cited “challenges our schools have experienced for decades – space constraints, class size imbalance and resource differences between the two elementary schools.” She adds that the Board has conducted rigorous due diligence, even delaying the reconfiguration from September 2023 to September 2024 in response to community concerns.

“The numerous emails the board has received and the public comments at board meetings include those who do not support reconfiguration and those who fully support it. Public sentiments are some of many pieces of information the board has to consider before voting on a final proposal.”

That’s fair. Yet the breach between the school board and community is bigger than a 1.8 square mile borough. Trust is hard to gain and easy to lose; parents are already talking about candidates for the next school board election. No, they don’t have the megaphones of richly-funded Moms for Liberty or National Parents Union, not even close. Yet they won’t be silenced. In school districts across the country, the rules have changed. River Edge is tiny but its significance is huge.