Cami Anderson on Newark Public Schools’ Revival Through Collaboration of Public Charter and Traditional Schools

January 27, 2016New York State Teachers Union Goes Wild

January 28, 2016UFT Attacks NYC Charters for Discriminating Against Kids with Disabilities, But He Misses the Real Story

Politico reports that UFT President Michael Mulgrew has resumed “UFT’s decade-long war against the city’s charter sector.” The reference is to a conference call with reporters earlier this week when Mulgrew promoted legislation that would require charter schools to enroll “sufficient numbers of high-needs students” or face sanctions.

The UFT chief is newly empowered, Politico notes. Governor Andrew Cuomo has weakly regressed on accountability, reversing himself on the Common Core and acceding to a moratorium on teacher evaluations linked to student outcomes. “Anything cracked will shatter at a touch,” said Ovid, and Mulgrew views Cuomo’s erosion of support for education reform as so many shards. He’s no doubt gleeful at recent news that a group of parents of children with disabilities have filed a civil rights complaint against his arch enemy Eva Moskowitz and her Success Academy charter school network.

Certainly, charter schools should welcome a wide spectrum of students: those with low or moderate disabilities, English Language Learners, economically-disadvantaged. But what about kids with serious disabilities? Are charter schools deliberately winnowing out these children?

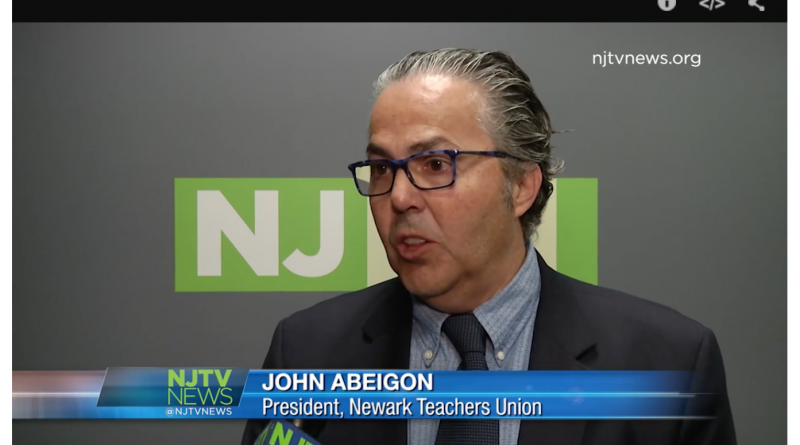

Mulgrew says that they are, and this line of attack is not restricted to New York City. On Friday, for example, Newark Mayor Ras Baraka assailed the city’s growing charter school sector for abandoning special needs students to traditional district schools. This meme has evolved into a primary talking point of anti-choice lobbyists.

Sometimes it’s useful to look at these arguments from a parent’s point of view. I have a son with multiple disabilities (I’ve written about him before) and, like all parents of children with moderate to severe impairments, we’ve had to make some tough choices about his educational placements.

My husband and I have always advocated for the “least restrictive environment” for our son, our local public school. This ethical and legal inscription is the foundation of disability law. Jonah, after all, is a community member and his disabilities shouldn’t exclude him from membership in our community.

Then there’s life. When Jonah turned 3, the year that he was eligible for special education services through our school district, there was no program for him. No one ever suggested that his high needs could be met through placement in our neighborhood school. In addition, parents of children with special needs are empowered by I.D.E.A. law to help choose the best placement for provision of services for their children.

That’s why New Jersey has a robust industry of private special education schools. In order to efficiently provide services and therapies for, say, kids with severe autism or those with behavioral disabilities or those with serious cognitive impairments, a school requires enough students of approximately the same age to support a classroom and appropriate staffing. Often, at least in N.J. with its crazy quilt of 591 school districts (more than any other state per square mile) the cohort is too small and so the child attends a private school or a larger school district. (Tuition and transportation is paid for by the local district.)

Charter schools are often even smaller, without those necessary cohorts. Parents know their high-needs special education children would be best served elsewhere. These are choices we make in order to maximize academic and social growth. For us, our district’s special education programming evolved and Jonah returned to the district in 7th grade, where he’s now a high school student.

Certainly, charters should not get a bye on serving special needs, nor should traditional schools. In fact, there’s an opening here for special education charter schools, like the New York City Autism Charter School.

And, just like traditional district schools, charters are stepping up to this challenge. The New York Post reports that “from 2008 to 2014, city charters doubled their percentage of enrolled students whose primary language isn’t English. And students with disabilities rose from 10.2 percent to 14.5 percent.” Also, see Marcus Winters’ report on charter schools’ superior of retention of special needs students, English Language Learners, and economically-disadvantaged children.

UFT’s Mulgrew has easy targets in Cuomo and Moskowitz. But his rhetoric disregards reality. All public schools – traditional and charter – should do a better job integrating children with high-needs disabilities into typical communities. We’ve got a long way to go but we’re all on the same path.