Newark’s Gateway U Kicks Off Training for Aspiring Teachers

February 28, 2024

Public Charter Students in Plainfield Inducted Into Prestigious Leadership Program

February 29, 2024Is Murphy Right To Say We Have the Best Schools in the Nation?

Yesterday, in a press release from the Governor’s Office, Gov. Phil Murphy touted his $56 billion proposed budget for Fiscal Year 2025, which includes almost $12 billion for schools. This record-high allocation, he says, represents his “commitment to maintaining New Jersey’s status as the best-in-the-nation public school system.”

We hear this claim a lot in the Garden State, from Murphy, from his DOE Commissioners, from NJEA leaders. However, as NJ Education Report readers know, while NJ performs really well, it’s hardly the “best-in-the-nation,” especially if that plaudit includes measures of educational equity and maintenance of high expectations. Now a new analysis from Chad Aldeman dives into what happens when state and national leaders are drawn to loose accountability rules and lower definitions of student proficiency.

Aldeman looks back at No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the Bush-era federal accountability program that everyone loves to hate because it set the bar for academic progress so high that it was impossible to meet. Every child, every school, every district, is going to make “Adequate Yearly Progress”?* Seriously? And the feds will dole out sanctions when, inevitably, states fail to meet that bar? When President Barack Obama came into office and released schools from those punitive sanctions, educators celebrated.

Maybe they celebrated too soon.

Aldeman argues that NCLB’s “accountability pressures,” which lasted from 2003-2013, were instrumental in a decade-plus of “small but significant gains” in student proficiency. When the Obama Administration (and the Legislature) weakened that federal oversight by replacing NCLB with a new accountability law called “Every Student Succeeds Act,” it “set off a decline in student performance across the country.” While COVID school closures didn’t help, these declines—Aldeman focuses on math, especially for the lowest-performing students—began well before 2020.

“When schools felt pressure from state accountability systems,” he says, “they increased their academic standards and boosted achievement in ways that had long-term benefits for students.” When schools didn’t feel that pressure, “achievement fell and gaps grew.”

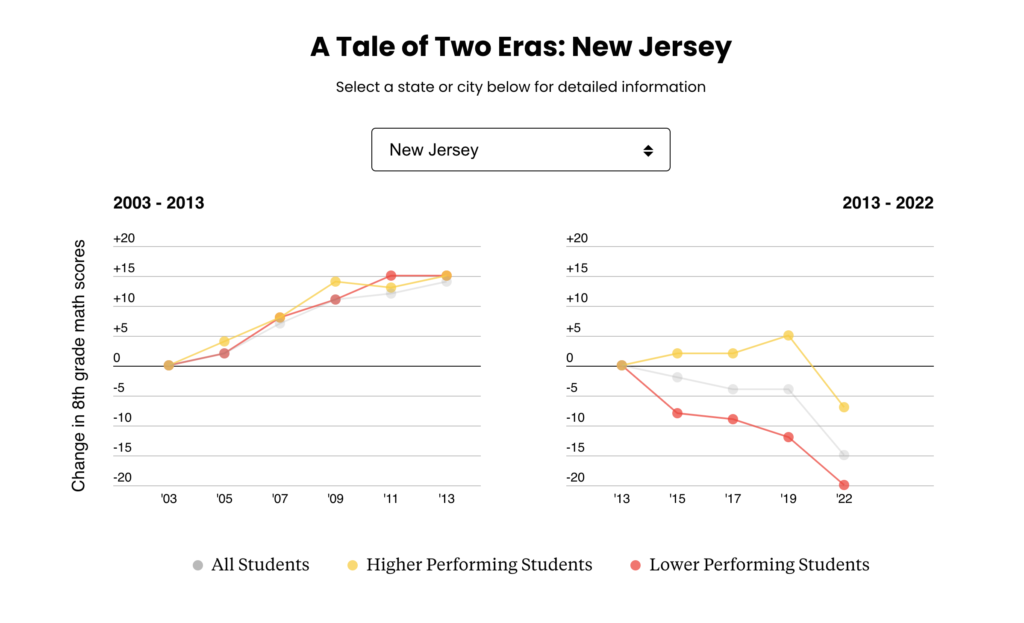

The piece includes a feature that allows you to look at each state. Here is New Jersey:

As you can see from the graph, from 2003-2013, the era of NCLB, student outcomes in math (based on that gold-standard of measurement, the National Assessment for Educational Progress, or NAEP) went steadily up, regardless of students’ starting points. In fact, lower-performing students made up so much ground they essentially closed the achievement gap.

But starting in 2012, when NCLB hit the dustbin, student achievement plummeted. Even if you ignore the 2022 NAEP scores as an artifact of the pandemic, the declines are huge. Sure, under the Obama Administration states had to reform standards, assessments, and teacher evaluations, but they no longer had to disclose whether or not students made Adequate Yearly Progress and could pick and choose which schools would be subject to state intervention.

The result in New Jersey?

Here, academic gains for our most disadvantaged students were erased; by 2019 math scores were way below where they were even in 2003, while higher-performing students (mostly) were fine. In effect, our achievement gaps became gulfs. Compared to the rest of the nation, New Jersey students lost ground in every cohort Aldeman uses—“All Students,” “Higher Performing Students,” and “Lower Performing Students”—with declines far larger than the rest of the country. For instance, in the “All Students” category,” the national decline is 18 points. In New Jersey it’s 29 points. For “Lower Performing Students,” the national decline is 21 points; in New Jersey it’s 35 points. For “Higher Performing Students,” the national decline is 13 points; in New Jersey it’s 22 points.

Plenty of pundits have pointed to other reasons for the these declines: union-maven Diane Ravitch says it’s Common Core’s fault, which raised learning standards; Fordham’s Mike Petrilli notes the timing of the Great Recession although, as Aldeman says, even during hard times school district increased their spending, especially in New Jersey. There may be other variables like student addiction to smartphones.

Yet New Jersey’s rate of decline stands out.

What does this mean for state departments of education and NJ’s own Department of Education?

It means that accountability matters. If the federal government isn’t going to hold states’ feet to the fire, the onus falls on individual state agencies to do this hard—and unpopular—work. “It may be time once again,” counsels Aldeman, “to ask schools to focus on the academic achievement of their lowest-performing students.”

We can boast all we want about our (important!) progressive funding formula, our LGBTQ-nurturing policies, our emphasis on social-emotional learning. But none of that is worth a hill of beans if our children, especially our most disadvantaged ones, can’t read or do math.

Maybe it’s time for an accountability reset.

*Note on the hysteria about “Adequate Yearly Progress”: NCLB included a category called “Safe Harbor,” which meant that even schools that underperformed could still function without intervention as long as they made even a tiny bit of progress.

5 Comments

How is proclaiming -New Jersey schools as “Best in the Nation”-not considered disinformation or misinformation? Pretty shameful. Perhaps, they think no one is paying attention except for those drinking the Kool-aide.

A disgraceful proclamation from a disgraceful governor.

Just curious. What is Commissioner Dehmer’s take on all this? Is he brimming of optimism or does he feel fit to remain silent and dance a quiet puppet’s dance?

DD.PAVEL to soon to tell. Hope springs eternal.

Fingers crossed, indeed, Ms. Waters.