LILLEY: NJEA Is Hiding $64 Million In Political Spending From Teachers Whose Dues Pay For It

September 18, 2023

Warning: New Jersey School Districts Are In For a Wild Ride

September 19, 2023It’s Time to Drop ‘Sexy’ Practices and Start Talking About a Science of Math

By now we’ve all heard about the Science of Reading, the dawning understanding that children don’t absorb literacy through osmosis and context clues but need direct instruction in phonics and practice in fluency..

Yet it’s well past the time, say researchers, to start talking about the Science of Math. Just like learning to read was crippled by the “whole language” movement promoted by Lucy Calkins and Columbia’s Teacher College (which earlier this month booted Calkins and her program out of town), student proficiency in math has suffered from a combination of factors, including poor teacher preparation, lack of attention to research-based pedagogy, lowered expectations, and a damaging effort to dress up math instruction in “progressive” drag. This experiment-gone-bad is exemplified in the notorious California Framework that, says experts like Tom Loveless, sacrifices “accelerated learning for high achievers in a misconceived attempt to promote equity,” injecting social justice tenets and ungendered language directly into curricula. EdSource ridicules the Framework’s primary architect, Jo Boeler, for mandating “trauma-induced pedagogy” that urges teachers to promote “sociopolitical consciousness” and take a “justice-oriented perspective” while embedding “environmental or social justice” in the math work given to children.

That may work just fine for Gov. Phil Murphy’s children, who can take Multivariable Calculus at their private school but not so fine for students at Trenton Central High, where the average score on the math SAT is 399, putting them in the bottom 15 percent nationwide.

Yet we’re starting to see nascent efforts to create a Science of Math. (Note: we’re missing a math version of Emily Hanford, who created the viral podcast “Sold a Story” that turned the Science of Reading into a movement, albeit one that the New Jersey Department of Education has yet to embrace).

What would a Science of Math look like? This is a critical issue, given that, according to the gold-standard NAEP scores from 2022, New Jersey fourth-graders dropped seven points in math proficiency and eighth-graders dropped eleven points. But isn’t that all a result of COVID school closures? Not so much: in 2019, during the previous NAEP testing, only four states had higher math proficiency scores than NJ students but in 2022 nine states had higher scores. (Math proficiency scores in Wyoming, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Florida, Wisconsin, North Dakota, Iowa, Utah, and New Hampshire are higher than NJ. Nationally, U.S. students rank 36th out of 79 developed countries on international math tests.)

We’d start with this: just like the Science of Reading emphasizes foundational skills, so would a Science of Math. That means explicit instruction in understanding numbers and their relationship to one another; being able to add, subtract, multiply and divide fluently; and having the ability to do word problems that are crucial to success at math’s higher levels.

“Direct and explicit instruction is what works best for reading and math in learners who are novices,” said Daniel Ansari, professor and Canada research chair in developmental cognitive neuroscience at University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario.

“Take every single thing that’s been written about the science of reading, and hit ‘find/replace’ for math,” said Sarah Powell, associate professor of special education at the University of Texas, Austin. She also leads a group of psychologists, cognitive scientists and math educators committed to evidence-based instruction, collaborating on a website called The Science of Math. “Just as we know there are foundational skills in reading, there is the same thing in math. Schools have been swayed by sexy practices, but that’s not how people learn.”

Just like revelations about the way kids learn to read has focused renewed attention on the way we prepare teachers to teach literacy, we must pay the same attention to the way we prepare teachers to teach math. Holly Korbey notes that the way many classroom teachers often shy away from memorization of math facts and timed tests has led to “the billion-dollar tutoring industry of Kumons and Mathnasiums,” where wealthy parents fund a “shadow education system of explicit instruction and practice,” buttressing inequities that already exist. Some of this disdain for direct instruction is elementary school teachers are often poorly prepared to teach math. “Many elementary teachers do not themselves feel adequately confident of their own basic math skills,” notes the National Council on Teacher Quality. “Potentially lacking confidence or sufficient content knowledge, they may dedicate less time to teaching math than students need, unsure of how to help their students avoid common misconceptions and errors.”

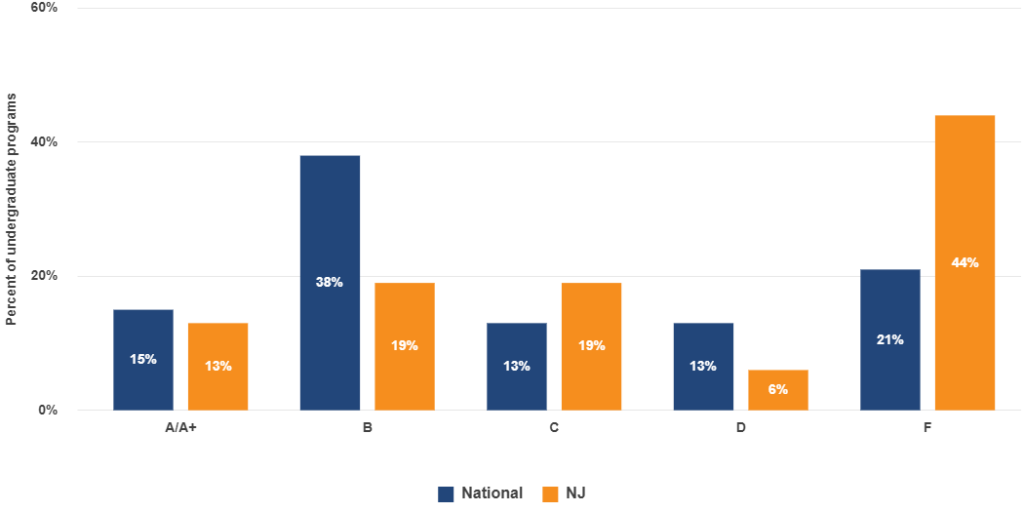

NCTQ rated teacher preparation programs; as NJ Ed Report reported this summer, NJ’s teacher preparation programs in reading were the worst in the nation in teaching core competencies. Our math preparation programs do slightly better. William Paterson, Fairleigh Dickinson, and Georgian Court got “B’s” but all other programs (they’re listed here) got “F’s.” “Addressing learning loss and building the math skills of young students,” warns NCTQ, “demands urgent action by all sectors of the education community, including educator preparation programs.”

Look at the graph. Among NJ undergraduate teacher preparation programs in math, 44% got “F’s.” That’s more than twice the rate of failure compared with programs around the country.

This may all sound abstract. Let’s make it real. Statewide, according to 2022 standardized state test scores, only half of NJ students are proficient in math. What about families who can’t afford to buy into the shadow tutoring industry of Kumons and Mathnasiums or send their kids to private schools? One out of ten students at Newark’s East Side High School meet grade-level expectations in math; other district school outcomes are similar. At this Asbury Park elementary school, the DOE leaves the field blank because student math proficiency is less than 10 percent, just as it does this Camden district middle school.Statewide, one out of six NJ eighth-graders meet expectations in math. Throw in our penchant for grade inflation—more so in math than in any other subject—and we’re sending high school graduates out into the world utterly unprepared for success in college and careers.

How’s that going? Today the Hechinger Report quotes Temple University math professor Jessica Babcock, who gave her freshman algebra students—all STEM majors– a quiz that she called a “softball,” asking students to subtract eight from negative six.

“I graded a whole bunch of papers in a row. No two papers had the same answer, and none of them were correct,” she said. “It was a striking moment of, like, wow — this is significant and deep.”

What we’re doing isn’t working. Can we summon the will to raise the bar?