College Signing Day Celebrates Achievements of Camden’s High School Seniors

May 2, 2023

Latest From Asbury Park: ‘This District Is an Absolute Joke,’ Say Teachers

May 2, 2023LASUSA: The Inequity and Uselessness of New Jersey’s Latest High School Graduation Test

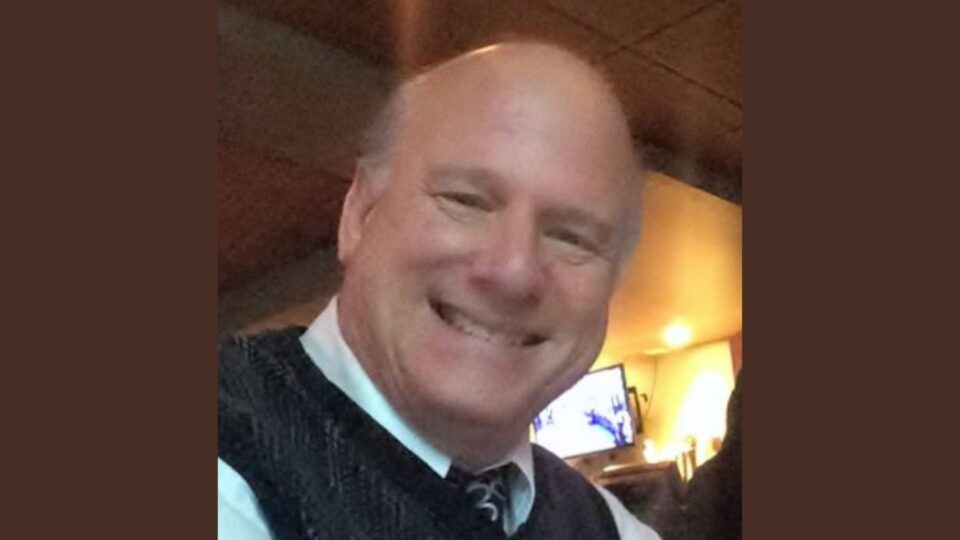

Michael LaSusa is the Superintendent of Schools in Chatham and was the 2018 New Jersey Region One Superintendent of the Year. This was first published at njspotlight.com.

The New Jersey State Board of Education has before it a proposal to change the “cut score” the Department of Education would like to establish for the state’s latest standardized test, the New Jersey Graduation Proficiency Assessment (GPA). The cut score is the minimum score deemed necessary to demonstrate proficiency, or pass. Beginning in 2024, students must pass this test in order to graduate from high school, and the argument has centered on whether the cut score should remain at 750 or be adjusted to 725 out of 850. The department proposes 725, while some opponents on the board believe that 750 will somehow ensure greater accountability and achievement for New Jersey’s students.

I would argue it is worth looking at what all these numbers mean in real life.

Since the introduction of PARCC in 2014-2015, high school seniors have faced a merry-go-round of high school assessments. Every year since then, including this current year, seniors have been able to qualify for graduation through a variety of measures, including by achieving a minimum score set by the education department on familiar college admissions tests like the SAT, PSAT or ACT. In doing so, this experience has helped school districts gather data and better understand the value — or lack thereof — in the high school assessments imposed upon our students.

The first administration of the GPA was last year. Our current seniors took the test as juniors, but fortunately for them, they may still draw on a passing score from another measure, like the SAT, to satisfy their graduation requirement. Here is a snapshot of how our students did.

In Chatham, 71% of our current seniors achieved a passing score on the English Language Arts section of the GPA. But it is worth noting that over 90% of Chatham graduates have gone on to attend four-year colleges every single year for the past 10 years. The 71% pass rate means that 96 of our current seniors did not pass the GPA. Of those, 70 scored between 725 and 749, the range at the center of the debate of the State Board of Education. And of those 70 students, 63 achieved a “passing” score on an alternative measure. For example, more than half of those students scored a 1,000 or higher on the SATs, with 12 students scoring in the 1,300s or 1,400s. Equally revealing, 60 of the 70 students have already been accepted into one or more four-year college or university.

Further illuminating, of those who had the lowest scores on the GPA, 80% of them had a SAT, ACT or PSAT score deemed high enough by the Department of Education to qualify for high school graduation and have already been admitted to a four-year college or university.

Not everyone can brush it off

It is the same story with the math section of the GPA. Last year, 42 Chatham seniors did not achieve a passing score, yet the vast majority scored high enough on the SAT, ACT or PSAT to demonstrate success on those tests. Three out of four have already gained admission to one or more four-year college or university.

It is easy in Chatham and communities like ours to brush off the various iterations of high school standardized testing as mere inconveniences. Our students and their families are predominantly well-resourced and possess a default orientation toward higher education. So even when a third of them cannot achieve a passing score on the GPA, they still proceed to take the SAT or ACT multiple times, still attend test prep courses, still find ways to visit colleges and still have a full menu of options beyond high school.

How many students in communities that are not as well-resourced are in this position? More than 60% of current New Jersey seniors did not pass the English Language Arts portion of the GPA and 50% did not pass the math section. How many of those students, by contrast, suffer through the GPA, feel small, and do not bother to take the SAT or ACT, thereby shutting doors that might otherwise offer opportunity because the state of New Jersey has communicated to them that they are not prepared to graduate from high school?

One might tell me that the GPA is new and that it simply needs to be calibrated. I would answer not only that the Department of Education is attempting to do this by adjusting the cut score, but also that Chatham saw the exact same pattern with PARCC tests. Of our dozens of students who could not achieve passing scores on those exams, almost all achieved strong scores on the SAT and ACT and almost all went on to four-year colleges and universities.

Now, one might tell me that the college admissions tests do not really measure much. To that I would say that Chatham graduates persist and graduate from college at very high rates. The percentage of our students who remain in college 16 months after graduation stands at about 90%.

A measuring stick

One might tell me that it is important for the state to utilize a uniform measuring stick for students across all districts. Acknowledging that the federal government may not permit the SAT or ACT for this purpose, I would cede the point but answer that the GPA (or whatever iteration of it comes next) should be administered — but not as a graduation requirement.

What is missing in the current debate about cut scores is a simple question: What is the point of the GPA in the first place? Chatham’s experience over the past eight years makes clear that there is no meaningful relationship between these tests and other, more established measures, like the SAT, ACT or AP exams. There is likewise no meaningful relationship between these tests and students’ admission to and success in college. There is no meaningful use of the results of these tests to diagnose or advance learning of individual students. What is the point then?

One of the reasons I have spent a career spanning more than a quarter century in public education is that I enjoyed school and was usually good at it. Even so, I ran away from the subjects or courses I found uncomfortably tough, and I still recall, decades later, how it felt to take an exam that made me feel frustrated and not smart. It is one thing for a student to feel that way due to a lack of preparation or the reality of reaching a point at which a subject has just become too complex. But it is quite another to pummel students with a test that serves no purpose and, worse, undermines and misaligns with their actual growth potential as evidenced through more established measures that actually support advancement toward higher education options.

Why are we doing this to kids?